Sri Lanka’s Economic Crisis: Awakening for the World’s Least Developed Countries

![]()

Dr. Sarder Ali Haider

Sri Lanka, a 22 million island nation, is undergoing an economic and political crisis, with demonstrators defying curfews and government officials resigning in bulk. The unrest is being fueled by the country’s worst economic crisis since it earned independence in 1948, with debilitating inflation sending the cost of essential items rising. According to experts, the problem has been building for years, driven by a bit of poor luck and a much of administrative incompetence.

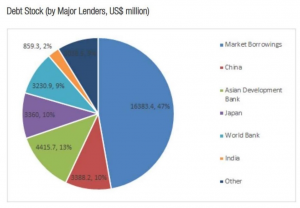

The Sri Lankan government has borrowed vast amount of money from international lenders over the last decade to fund public services. This borrowing spree has coincided with a succession of hammer blows to Sri Lanka’s economy, ranging from natural disasters such as severe monsoons to man-made disasters such as the government’s prohibition on artificial fertilizers, which wrecked farmers’ harvests. These concerns were exacerbated in 2018, when the President’s dismissal of the Prime Minister precipitated a constitutional crisis; the following year, when hundreds of people were killed in Easter bombings at churches and luxury hotels; and beginning in 2020, with the arrival of the Covid-19 pandemic.

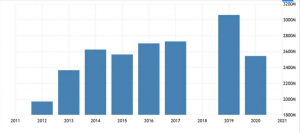

Sri Lanka was ahead of many Asian nations when it gained independence from the British in 1948, with economic and social indicators comparable to those of Japan. The following comparable data may provide insight into Sri Lanka’s economic situation throughout time:

- In 1948, a Sri Lankan’s life expectancy at birth was 54 years. This was slightly less than Japan’s 57.5 years. In 1950, Sri Lanka’s infant mortality rate was 82 deaths per thousand live births, compared to 91 deaths per thousand live births in Malaysia and 102 deaths per thousand live births in the Philippines.

- Sri Lanka’s unadjusted school enrollment rate as a percentage of the 5-19-year age group is 54%, compared to 19% in India, 43% in Korea, and 59% in the Philippines.

All of this was feasible because Sri Lanka had previously maintained an independent macroeconomic policy. The economy has been eased and tightened in response to changing circumstances, most notably foreign exchange fluctuations. In the 1970s, there were Armed revolts against Sirimavo Bandaranaike’s communist government (world’s first female head of state of a republic; pro-Soviet Union). In 1977, a pro-US right-wing government took control. Sri Lanka’s economy shifted significantly away from a socialist model. Sri Lanka was the first South Asian country to liberalize its economy in the 1970s, whereas India initiated their own economic liberalization plans in 1990s and China did in 1980s.

Sri Lanka was the first country to implement robust business rules. Imports were regulated to protect domestic industry until domestic enterprises became strong enough to compete on product quality and price with imported goods. Although India and China did not implement the IMF and World Bank’s recommended “shock therapy”[1], Sri Lanka implemented it very seriously. According to IMF, World Bank and US Department of Treasury’s advice, Sri Lanka liberalized rapidly deregulating, privatizing, and opening the economy to international competition. Markets were opened up for competition (e.g., rice and wheat imports from Japan/US) too rapidly, before strong financial institutions were established. The domestic producers could not compete with the imports from industrialized nations, before Sri Lanka’s own industries had been upgraded to a certain level.As a result, jobs were destroyed faster than new jobs were created.

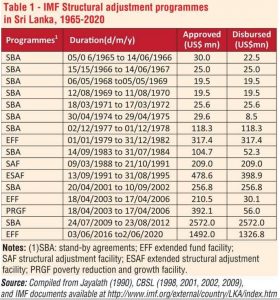

Under the IMF’s Structural Adjustment Programs, financing for industrialization were made contingent on the government adhering to their policies. These IMF-led reforms were accompanied by a campaign against trade unions.

In 1980s onwards the Sri Lankan Civil War was fought between the LTTE and the Sri Lankan government forces. The LTTE controlled territory in the island’s north and east. Numerous governments have designated the LTTE as a terrorist group. The Sri Lankan Civil War ended in 2009, with the LTTE militarily defeated. The government reclaimed control of the country’s north and east. Economic hope was restored after the conclusion of the war, as consumer demand increased.

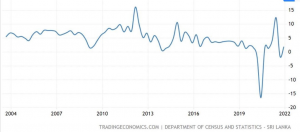

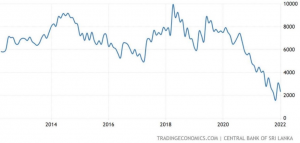

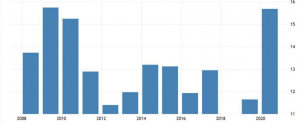

On the other hand, Sri Lanka’s economy remained reliant on colonial-era exports of tea, rubber, and clothes. The decade-long decrease in global commodity prices has had an effect on exports of these goods (2012 to 2022). Sri Lanka’s economic growth rate has slowed significantly since about 2012, as global commodity prices have fallen. Following 2012, the rate of GDP growth dropped dramatically. The postwar acceleration of GDP slowed rapidly, and in the absence of export growth, the current account deficit widened.

Sri Lanka secured a 36-month extension of the EFF agreement with the IMF in 2016 for US$1.5 billion to pursue an economic reform agenda. The IMF’s conditionality was to decrease the fiscal deficit to 3.5 percent of GDP by 2020. The other IMF conditionality was modeled after the traditional Washington Consensus:

- Reform of tax policy & administration;

- Control over expenditures;

- Commercialize state enterprises;

- Exchange rate flexibility;

- Boost to competitiveness; and

- A free investment environment.

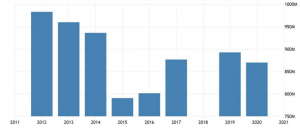

After three years, the IMF commended Sri Lanka for its “commitment to the EFF-supported program,” “efforts to pursue revenue-based fiscal consolidation, with a well-targeted 2019 budget,” “strengthen reserves while allowing for greater exchange rate flexibility,” and “prudent monetary policy.” In actuality, the Sri Lankan people’s 2016-19 experience with IMF reforms was very unpleasant. GDP growth rates have slowed, although the corporate tax rate has been reduced from 28 to 24 percent. The revenue-to-GDP ratio decreased, but governmental debt increased by 30%.

In 2019, Gotabaya Rajapaksha was elected President on a Sinhala nationalist platform. Since 2019, two significant events have wreaked havoc on Sri Lanka’s economy:

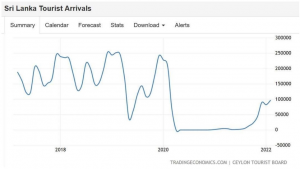

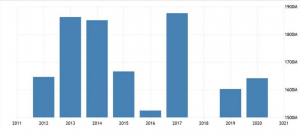

- Tourism

- Sri Lanka was a popular tropical destination for western tourists. In 2019, the Easter bomb blasts in three churches and three hotels in Colombo, killed about 253 people.It created a huge decline of tourists.

- Since 2020, COVID-19 pandemic led to a huge fall in the flow of tourists to Sri Lanka.

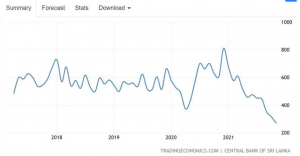

This led to major strains on the foreign exchange reserves

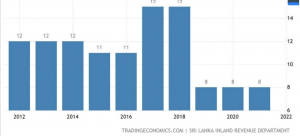

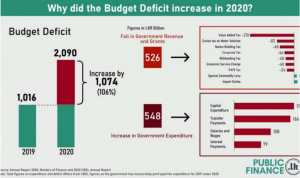

- In December 2019, the new President Gotabaye Rajapakse, in a thoroughly ill-advised move, cut VAT rates from 15% to 8%. Other taxes were also abolished, like, the “nation building tax” of 2%, the economic service charge and PAYE tax.

As a result, prior to the pandemic, Sri Lanka had one of the lowest indirect tax rates in the world. This resulted in a significant decline in indirect tax receipts. GST/VAT revenue decreased from 443,877 million Sri Lankan Rupees in 2019 to 233,786 million LKR in 2020, a nearly 50% decrease in tax revenue.

Pandemic Impact

The pandemic hit in March 2020, and it made the bad worse.

- Tourist inflows and tourism revenues fell further.

- Exports of tea and rubber declined due to lower demand.

Remittances, another booster to the foreign exchange reserves, also fell as Lankans across the globe lost jobs.

The government was forced to increase budget spending as a result of the pandemic. In light of declining income, the fiscal deficit exceeded 10%. Regrettably, Sri Lanka lacks fiscal deficit management provisions. In February 2022, the IMF highlighted three causes of Sri Lanka’s economic crisis:

- Pre-pandemic tax cuts,

- Weak revenue performance and

- Higher lockdown spending

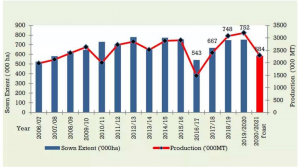

Food shortage despite of Monsoon

During the epidemic, neighboring Asia’s tourism-dependent economies, including as Thailand and Indonesia, changed their focus to agricultural, absorbing the labor. However, Sri Lanka was unable to replicate this. Numerous advisors informed Rajapakse that Sri Lanka’s forex pressure could be alleviated if the country ceased fertilizer imports. Rajapakse positioned himself as a savior of organic farming, announcing a ban on all chemical fertilizer imports beginning in May 2021. Without proper scientific knowledge, the abrupt and complete abandonment of chemical/industrial agriculture resulted in a decline in farm output. Farmers and dealers lost their livelihoods, and despite ample monsoons, rice production decreased.

The situation forced the Government of Sri Lanka to import food which costed more forex drain.

Rajapakse’s organic misadventure was backed by a slew of Western environmental groups that impose policies on developing nations but ignore rich nations’ pollution. Sri Lanka’s organic farming strategy has been a colossal failure. Agriculture was resilient in the majority of countries during the pandemic. However, the situation was reversed in Sri Lanka. According to the IMF, “The chemical fertilizer restriction is having a more adverse effect on agricultural production than anticipated. The recovery is projected to be slowed by a temporary ban on the use and importation of chemical fertilizer, which will have a detrimental effect on agricultural productivity, as well as by the negative impact of currency shortages and the suspension of some imports “‘.

As agricultural production declined, food shortages resulted in inflation, necessitating food imports. Tea and rubber production and exports were affected. Thus, a measure intended to alleviate pressure on foreign reserves ended up inadvertently increasing that strain.

Bangladesh’s economy is more stable than Sri Lanka’s tourism-dependent economy, as it is based on textile exports, remittances, and agriculture. Sri Lanka’s economic crisis teaches Bangladesh and other developing countries some critical lessons. Economics and politics are inextricably linked and mutually impact one another. Resources are limited and have multiple uses. Limited resources should be invested in ways that maximize the short- and long-term benefits to society. Economically unsound investments should be avoided in order to mitigate risk concerns.

[1] The IMF promotes international monetary cooperation and provides policy advice and capacity development support to help countries build and maintain strong economies. The term “Shock Therapy” was an invention of the media and a modification of Milton Friedman’s phrase “Shock Policy.”