Myanmar’s Drug-An Expanding Concern for South and Southeast Asia

![]()

Parvedge Haider

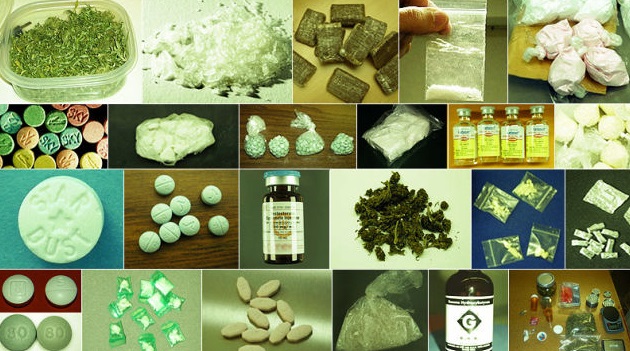

The practice of massive production of different kind of drugs is not new for Myanmar. With the passage of time, there are changes in the type of drugs. But in maximum cases, the old one also remains. Though the country has made a new policy[1] to address this issue, it is debatable how far it will be able to arrest that as long as the users are punished more than the producers. For decades, there is huge drug production in Myanmar, particularly in Shan state, which forms part of the infamous “Golden Triangle”[2] alongside Thailand and Laos. Traditionally, the people of Myanmar are closely associated with the production of heroin, and until 1991 was the largest producer of the drug in the world, before being overtaken by Afghanistan. The Myanmar Opium Survey 2018[3], published by the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), estimates that areas under opium poppy cultivation in Myanmar covered 37,300 hectares in 2018, down from 41,000 hectares a year earlier, continuing a downward trend that started in 2014 but still the vast majority of Myanmar’s poppy is grown in Shan state. Though the poppy cultivation state has been reduced since 2010, drug production in the country and particularly in Shan state has been shifted sharply to methamphetamines, including yaba and the more expensive crystal meth, also known as “ice.”[4]

The UNODC report noted a “sharp increase” in the supply and demand for synthetic drugs, particularly methamphetamine, across East and Southeast Asia. Synthetic drugs are chemically-created in a lab to mimic another drug such as marijuana, cocaine or morphine etc. These types of drugs typically create a different effect on the brain or behavior; these are created in illegal labs, their ingredients and strength are almost impossible to know. There are more than 200 identified synthetic drug compounds and more than 90 different synthetic drug marijuana compounds. It is reported that out of the 11 countries in the region sharing drug data with UNODC, nine are now reporting methamphetamine as their primary drug of concern, as opposed to a decade ago when four countries were reporting methamphetamine and seven heroin. A recent report by the International Crisis Group narrates that Shan state has emerged as “one of the largest global centers” for the production of crystal meth, the common name for crystal methamphetamine, a strong and highly addictive drug that affects the central nervous system. It comes in clear crystal chunks or shiny blue-white rocks. These types of drugs are termed as “ice” or “glass,”; it’s a popular party drug. Usually, users smoke crystal meth with a small glass pipe, but they may also swallow it, snort it, or inject it into a vein[5]. People say they have a quick rush of euphoria shortly after using it. But it’s dangerous.

According to International Crisis Group report (January 8, 2019), Shan State has long been a center of conflict and illicit drug production, initially heroin, then methamphetamine tablets. Good infrastructure, proximity to precursor supplies from China and safe haven provided by pro-government militias and in rebel-held enclaves has also made it a major global source of high purity crystal meth. Drug production and profits are now so vast that they dwarf the formal sector of Shan State and are at the center of its political economy. This greatly complicates efforts to resolve the area’s ethnic conflicts and undermines the prospects for better governance and inclusive economic growth in the state.

In January 2018, the law enforcing agencies in Myanmar seized 30 million meth pills, as well as two tons of ice and heroin, which might be valued at US$54 million[6]. Authorities in Myanmar have taken some measures to control the drugs issue in the country, although there are questions about how effective they have been. In February 2018, authorities announced the National Drug Control Policy, which recommended tackling the drug issue and promoting international cooperation. At the time of its release, the new policy was largely welcomed by the civil society groups and non-government organizations advocating for a more progressive drugs policy in Myanmar. However, almost a year since the policy was announced, it’s not clear how effective it is being implemented.

According to UNODC, 48% of Myanmar’s 60,000-80,000 prisoners are detained for drug related offences, with the percentage of drug-related offenders as high as 70-80% in some prisons (such as in Myitkyina and Lashio)[7]. This is a significant financial and management burden to the prison system. Detaining of drug users not only burdens the criminal justice system but also carries negative social and health consequences for families and communities, both when users are in prison and after they are released.

One of the important reasons for the enormous opium cultivation in Myanmar is to reduce the poverty of the general people. A good percentage of available lands are not suitable for the cultivation of other crops. At the same time, due to inadequate communication facilities, the general people are unable to transport their product in time. Production is mainly concentrated in the Shan and Kachin states. Due to poverty, opium production is attractive to impoverished farmers as the financial return from poppy significantly more than that of rice[8]. It makes them unwilling to cultivate the crops and fruits. Moreover, opium is being used to produce some of the traditional medicines in Myanmar[9]. There are important cultural and health-related reasons for the cultivation of opium. Due to its medicinal values as a pain-relieving, cough suppressant and treatment for diarrhea, opium has been the main traditional medicine that villagers in the remote highland areas rely upon to cure most of their sicknesses. So, by producing opium, the poor general people at least can run their day to day life.

There might be a number of reasons on the Myanmar side to continue cultivating opium and producing various kind of synthetic drugs but it is becoming highly detrimental to the neighboring countries, specially Bangladesh. Myanmar’s drugs are causing incapability and instability of the thousands of youths in Bangladesh. Moreover, this illegal trade is creating transnational organized crimes and trans-border crimes. It is also fueling terrorism in the southeast part of Bangladesh. Already a good number of internal problems of Myanmar have created enormous tension to its neighbors; in the plea of poverty reduction, traditional practice and ingredients of producing medicines, Myanmar cannot create a problem for its neighbors. World community and international organizations might have an eye on this serious issue.

Parvedge Haider

Researcher, Regional Politics and CHT

Email: parvedgehaider5235@gmail.com